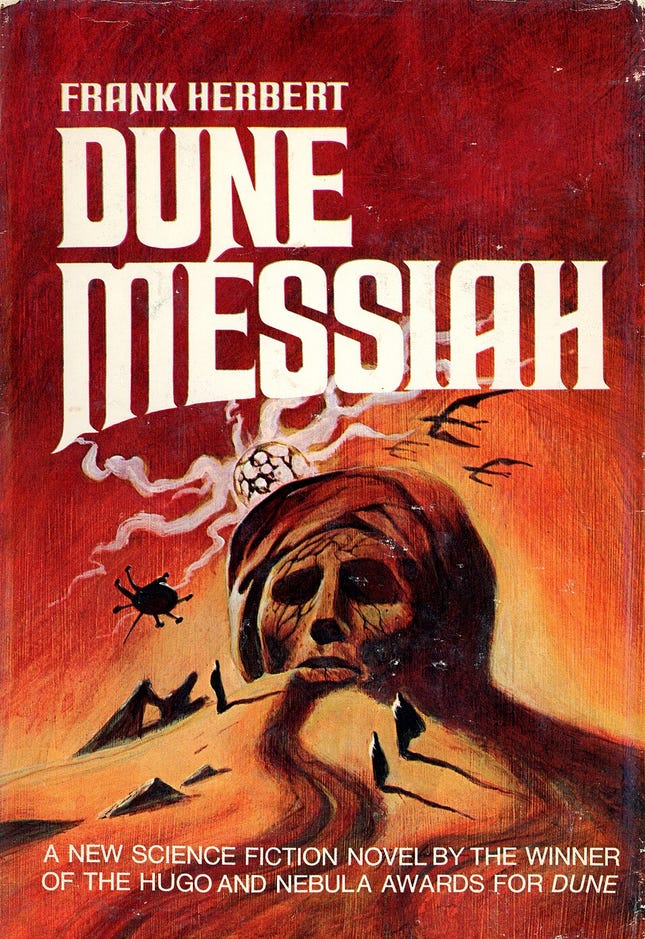

Dune Messiah (Dune #2)

Frank Herbert

A lot has happened in twelve years. The desert planet Arrakis is now the seat of power for the god-emperor Muad'dib and his holy sister. Water is plentiful as the jihad, guided by prescient knowledge of futures which may be, sweeps ten thousand worlds into the greatest empire in history. For the remnant who resist or resent Muad’dib’s rule, one question alone remains: how do you kill a god?

The second book of Frank Herbert’s “Dune” series upset my expectations in the best possible way. Perhaps I was subconsciously misled by my appreciation for Isaac Asimov’s “Foundation” series, which shares some surface similarities. Both deal with themes of power, empire, religion, and prescience. I could even draw some interesting parallels between Herbert’s Muad’dib and Asimov’s Mule. Probably, then, I anticipated an Asimovian sequel in which Muad’dib’s power starts to expand beyond Arrakis even as he fights to avoid his “terrible purpose” of bloody jihad. But where Asimov’s interest lies in the mechanics of power, Herbert’s lies in the deep currents that bring empires into existence only to dash them on the rocks of their own success.

In this, Herbert’s debt to Ibn Khaldun looms large. The medieval Islamic scholar constructed a theory in which strength originates outside of empire, where scarcity and hard living forge collective clan virtues that empower tribes to invade and topple states, only themselves to fall as their virtue succumbs to riches and soft living, inviting new and virtuous tribes from the hinterland to invade as the cycle restarts. This theory runs beneath every wind-blown ridge in “Dune Messiah.” The sheer scale of Muad’dib’s victory softens the hard-edged virtues of Fremen warrior culture, transmutes a pure and living faith into the sprawling theocratic bureaucracy of the Qizarate, and strips morality of power by reducing it to law, regulation, and the commands of a god-emperor. How long can a government stand when virtue, faith, and morality are hollowed out by the very success they created?

Though this Ibn Khaldunian perspective drives the narrative, "Dune Messiah" is a book thick with themes, from ecology to gender politics to the power of language to the tensions that thrum at the intersections of science and faith. The theme that struck me most forcefully, though, was the futility of struggle against a universe driven by blind and remorseless eternity. Some try to control eternity through reproduction or technology, like the Bene Gesserit and the Bene Tleilax, respectively. Some try to control it through faith or superstition.

But neither biology nor bioengineering nor priestcraft nor mysticism can resist forces that existed long before you did, and will exist long after your memory is forgotten. Even a god-emperor, who peers deeply enough into time to sense its pitiless gears, can only grope for the least horrifying alternative available. Calm acceptance of fate is the only rational choice in a universe such as this, for in the sacred words of Muad’dib as recorded in The Stilgar Commentary, “You do not beg the sun for mercy.”

Author: Frank Herbert

Series: Dune

Genres: Fiction, Science Fiction, Space Opera