Churchill: Walking with Destiny

Andrew Roberts

British author C. J. Sansom wrote a novel of alternative history set in 1952 and entitled “Dominion.” He selected May 1940 as his point of divergence with the appointment of Lord Halifax rather than Winston Churchill as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom. Sansom envisioned a Britain nominally independent of Nazi Germany, but humbled and subservient following the fall of France and a negotiated peace.

Sansom came in for criticism over his portrayal of real-life people as collaborationists with Hitler’s regime, but the novel illustrates a perennial question. Does destiny pivot on individuals, or do “great men” merely ride waves that would’ve carried someone else in the same direction?

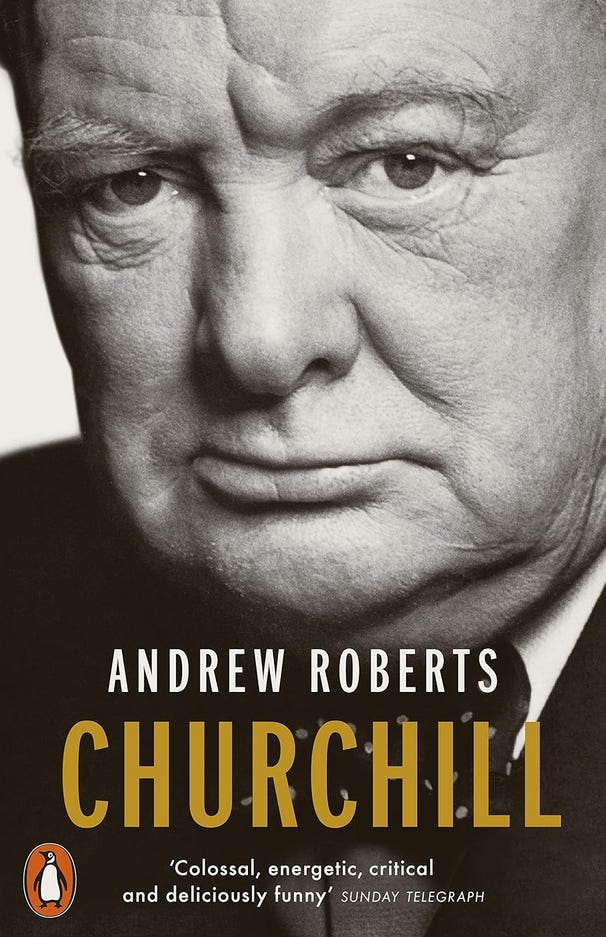

Andrew Roberts, I suspect, takes the view that great men do turn the pages of history. His biography of Churchill, enriched by troves of contemporary documents only unsealed in the 21st century, frequently points in this direction. Given that Roberts is a Thatcherite peer in the House of Lords, I don’t find it strange that he sees Britain’s indispensable man in the conservative, aristocratic, Victorian, and unabashedly imperialistic Winston Churchill.

For what it’s worth, I agree with what I think is Roberts’s view. I believe destiny can hinge on a single person, and I believe that without Churchill we might be living in a darker world. Two thoughts recurred to me in the course of reading about the British Bulldog.

First, the times make the man. Deferential though Roberts is to his subject, he didn’t set out to write a hagiography. Churchill was a hard charger, stepping on every toe as he shoved his way to the top. His mix of romanticism, impudence, and self-promotion earned him enemies who were only too willing to kick him aside after his name became entangled with the disaster of Gallipoli in 1915.

But for Hitler, Winston Churchill would’ve faded into the footnotes as a brilliant but erratic young aristocrat, mildly racist and sexist, cursed with his father’s talent for botching politics, and washed out by his own miscalculations and hubris to wither on the back benches.

But Hitler rose. And with this rise comes my second thought, that the man makes the times. Churchill understood the Nazi threat sooner than most, enduring years of abuse as a warmonger desperate for publicity. When war came, no one else had greater moral capital to lead Britain into its finest hour.

Powerful voices urged negotiations to end an unwinnable war, but Churchill refused to live in a world run by Nazis. He injected his own determination into the empire’s veins, and kept hope burning in occupied Europe as illustrated by an entry in Anne Frank’s diary: “I must mention one shining exception [to boring political radio]—a speech by our beloved Winston Churchill is quite perfect.”

He wasn’t perfect, but he was perfect for his time. Roberts’s biography brims with anecdotes of Churchill’s many faces: infuriating, playful, stubborn, gracious, ruthless, boyish. I see a touching symbolism in his lifelong infatuation with butterflies. Even as his mind faded near the end of his life, he still delighted in hours spent among the butterflies. How fitting that the man who drove Hitler to shoot himself in a bunker ended his days surrounded by the beauty of the world he fought so hard to preserve.

Author: Andrew Roberts

Genres: Nonfiction, History, Biography

Tags: World War II