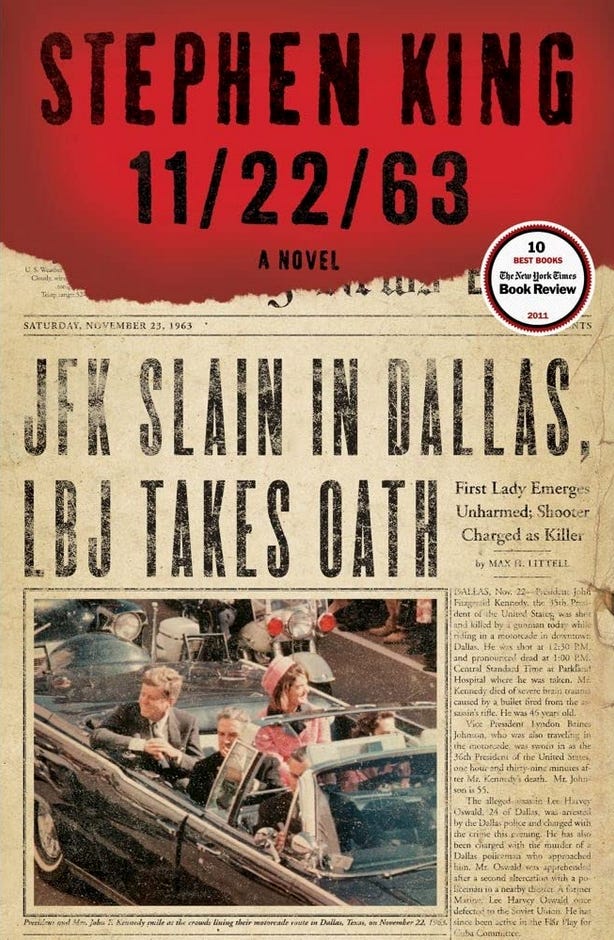

11/22/63

Stephen King

My favorite Cyanide & Happiness webcomic features a man who steps out of a time machine triumphantly proclaiming he’s killed baby Hitler, only to be arrested by people who’ve never heard of Hitler but certainly heard this guy confess to killing a baby. Stephen King plays with this conundrum in “11/22/63.” What if you could save President John F. Kennedy, potentially averting the wave of assassinations and violent unrest that haunted the 1960s and scarred the future? And what if all you had to do was kill a man who hadn’t done anything yet?

I like King’s typically atypical twist on time travel. Just as he gave a fresh spin to the zombie apocalypse in “Cell,” King introduces clever rules to make the past resistant but not impervious to change. This heightens the stakes — the bigger the change, the more dangerous the resistance. Also clever is the choice of the Kennedy assassination as the inflection point. The mystery that still shrouds the murder means that averting it is not necessarily as simple as exchanging Lee Harvey Oswald’s life for Kennedy’s. What if Oswald didn’t act alone, or actually was the patsy he claimed to be?

What slows the story is the way King sharpens the stakes by giving his protagonist a love interest and a beautiful life in the years spent surveilling the Oswalds. King’s deliberately-paced portrait of the fictional small town of Jodie, Texas leaves an impression America lost something between now and then. This, of course, is partly the point. What if you could save America from the national gutting it experienced on November 22, 1963? Would it be enough to preserve these small-town values, averting the paranoia and violence that splintered outward from Dealey Plaza into the soul of the nation?

The question is unanswerable and perhaps overly nostalgic, but makes for good stakes. That said, it’s tough to interweave parallel but wildly different plotlines. A time-traveling assassin tracking Lee Harvey Oswald is not the same story as a high school teacher finding love in a small town. These threads weave together tightly and meaningfully by the end, but it takes a while to get there.

“11/22/63” is still a good read with enough classic King to keep things interesting, from the mysterious Yellow Card Man to an interlude in the Derry of 1958 to the sensation that some eldritch thing is always sliding uneasily beneath the surface of what we call reality. I just think King set himself an ambitious task, succeeding better than most would, but constrained by the nature of the structure he set out to build. Perhaps, and I don’t know that he would, but perhaps he would appreciate my observation that narrative can be just as obdurate as the past.

Author: Stephen King